Are lower oil prices good news? Not really, if it means the world is sinking into recession.

We know from recent past experience and from common sense that higher oil prices are a drag on oil importing economies, since if more $$$ are spent on the same amount of oil, there is less to spend on discretionary goods and services. In addition, oil money sent to oil exporting countries is likely to be spent within those economies, rather than being reinvested in the oil importing country that the funds came from.

igure 1. A rough calculation of expenditure (in 2011$) associated with oil imports or exports, based on 2012 BP Statistical Review data, for three areas of the world: the Former Soviet Union (FSU), the sum of EU-27, United States, and Japan, and the Remainder of the World. (Negative values are revenue from exports.)

A rough calculation based on 2012 BP Statistical Review data indicates that the combination of the EU-27, the United States, and Japan spent a little over $1 trillion dollars in oil imports in 2011–roughly the same amount as in 2008. Governments have been running up huge deficits and have been keeping interest rates very low to cover up this damage, but it is hard to make this strategy work. The deficit soon becomes unmanageable, as the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) countries in Europe have recently been recently been discovering. The US government is facing automatic spending cuts, as of January 2, 2013, because of its continuing deficits.

Furthermore, lower interest rates aren’t entirely beneficial. With low interest rates, pension funds need much larger employer contributions, if they are to make good on their promises. Retirees who depend on interest income to supplement their Social Security checks find themselves with less income. The lower interest rates don’t necessarily have a huge stimulatory impact on the economy, either, if buyers don’t have sufficient discretionary income to buy the additional services that new investment might provide.

Below the fold, we will discuss what is really happening with oil prices, and consider reasons why lower oil prices may be a signal that the world is again headed for deep recession.

Oil Supply is Not Rising Enough

The big issue is that oil supply is not rising enough–and hasn’t been for a long time.

Figure 2. Actual and fitted oil consumption, based on BP 2012 Statistical Review. Fitted trend value of 2.0% is based on 1983 to 1989 actual data; fitted trend value of 1.6% is based on 1993 to 2005 actual data.

When oil supply doesn’t rise fast enough, there are two opposite effects that can take place:

Figure 3. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent oil prices, in US dollars, based on weekly average spot prices from the US Energy Information Administration.

(1) The most common effect is that prices will go higher. This can be seen in the upward trend in prices in the last eight years.

(2) The other effect is that prices can drop quite sharply, as they did in late 2008. This happens when parts of the world are entering recession, and their demand is decreasing.

It seems to me that this second effect may be happening this time around, as well. The down-leg we are seeing in the prices may have farther to go, as the recession plays out.

One Problem Area: PIIGS Oil Consumption is Declining

If we look at three-year average growth rates for the PIIGS, we find that there is a close correlation between oil growth, energy growth, and GDP growth. Furthermore, in recent years, a growth (or drop) in energy use seems to proceed a growth (or drop) in GDP. Not all of this energy is oil, but for the PIIGS countries, even natural gas is a relatively high-priced import. Recently, oil consumption has been declining sharply, which could imply further economic contraction.

Figure 4. A comparison of average three-year growth rates on three bases: GDP, oil consumption, and total energy consumption. GDP from USDA Research Real GDP database; oil and energy consumption from BP’s 2012 Statistical Review.

Furthermore, data from the Joint Organizations Data Initiative (JODI) shows that recent PIIGS oil demand is down even more. Comparing oil demand for February-April 2012 with February-April 2011, demand is down by 10% for the five PIIGS countries combined. This would suggest that these countries are sliding more deeply into recession.

US Oil Consumption Is Also Shrinking

US oil consumption is also shrinking.

Figure 5. US average consumption of petroleum products, during the months January to April, based on data of the US Energy Information Administration.

US oil consumption shrank by 3.2%, comparing the first four months of 2012 with a similar period of 2011. This is concerning, because based on Figure 5, it looks much like a repeat of the pattern that took place in the 2005 to 2009 time period. Oil consumption was stable during the period 2005 through 2007, then dropped in early 2008 by an amount not too different from the decrease in oil consumption from 2011 to 2012. The bigger step-down in oil consumption came in 2009, after oil prices dropped, and the follow-on effects (reduced credit availability, layoffs) had started. Now oil consumption has been relatively stable in 2009 to 2011, but there has been a step down in consumption in 2012, similar to the step-down in early 2008.

If Oil Prices Stay Down, or Drop Further, Not All Oil is Economic

Oil prices make a difference in a company’s willingness to drill new wells. For example, oil sands production in Canada is quoted as being not economic below $80 barrel, and the West Texas Intermediate price is below that level today. In most instances, existing production will be continued, but new production will be stopped. There are quite a few other types of oil extraction elsewhere (for example, arctic extraction, new very small fields, very deep oil wells, steam extraction outside Canada) that may not be economic at lower prices.

Saudi Arabia makes frequent statements about offering its production to keep prices down, but if a person looks at production patterns in the past few years, they have been highest when oil prices have been highest. Production has dropped as oil prices drop. So a rational person might conclude that oil wells which cannot be operated continuously (of which there are some in Saudi Arabia) tend to be operated when prices are highest, and turned off when prices are lower, thus maximizing profits. As oil prices drop this time around, we can expect Saudi Arabia and others to find excuses to save production until prices are higher.

Countries exporting oil depend on the revenue from the sale of oil, plus taxes on this revenue, to help support country budgets. As oil prices drop, governments find themselves with less money to fund promised public welfare programs. This dynamic can cause lower oil prices to lead to political instability in some oil exporting nations.

Thus, any drop in oil prices tends to be self-correcting, but not until oil production drops, prices of other commodities drop, and many workers have been laid off from work. We saw in 2008-2009 that this kind of recession can be very disruptive.

What’s Ahead?

We can’t know for certain, but the big issue is chain reactions, as one problem causes other problems around the globe. We are dealing with an interconnected international economy. If countries are in financial difficulty, their banks are likely to be downgraded as well. Other banks hold debt of the bank, or of the country in difficulty, or derivates relating to a possible default of the country or bank. If default occurs, these other banks may be affected as well. Thus one default may start a chain of defaults.

Banks that are facing difficulty (inadequate capital, poor ratings), are likely to become more selective in their lending. This makes it even more difficult for small businesses to obtain loans, and may lead to layoffs.

A country which appears to be near default is likely to face higher interest rates, making its cost of borrowing higher. The higher interest costs, by themselves, push the country closer to default.

One of the issues with high oil prices is that the higher prices, especially among oil importers, give rise to a kind of systemic risk that affects many kinds of businesses simultaneously. High oil prices tend to do several things at once: lower the real growth rate, make it more difficult to repay loans, and increase the unemployment rate. All of these issues make it more difficult for governments to function, because governments play a back up role. If workers are laid off from work, governments are expected to compensate laid-off workers at the same time they are collecting less in taxes and bailing out distressed banks. This type of systemic risk leads to the possibility of multiple government failures.

Promises of Future Oil Capacity Growth Aren’t Very Helpful

We keep reading articles claiming that world oil production will grow by some large amount by some future date. One of the latest of these is by Harvard Kennedy School researcher (and former oil company executive) Leonardo Maugeri, called Oil: The Next Revolution. According to the report, “Oil production capacity is surging in the United States and several other countries at such a fast pace that global oil output capacity is likely to grow by nearly 20 percent by 2020, which could prompt a plunge or even a collapse in oil prices”.

Even if the forecast were true (which I am doubtful), the problem is that this is simply too late. We have been having oil supply problems for quite some time–since the 1970s. The rate of oil supply growth keeps ratcheting downward, and the world keeps trying to adapt, with recessions to show for its efforts. (James Hamilton has shown that 10 out of 11 recent recessions were associated with oil price spikes.)

We don’t have time to wait until 2020 to see whether the supposed additional capacity (and production) will actually materialize. We have a problem right now. The downturn in oil prices and the reduction in demand in the US and PIIGS is looking more and more like the current oil price spike (of 2011 and early 2012) may give rise to yet another recession. Based on our experience in 2008-2009, and our difficulties since then, this recession may be severe.

Pingback: Fuel, Money, Climate … | Economic Undertow

If exporters cut back on production to maintain prices, that will serve only to drive the general economies faster into depression.

If you are correct in your analysis, Gail, then we are in for a hell of a storm.

That unfortunately sounds right. I wish I could come up with happier answers.

Pingback: WHAT FALLING OIL PRICES REALLY MEAN « The Burning Platform

So, rising oil prices are bad, and declining oil prices are bad. Rising oil consumption is bad, and declining oil consumption is bad. You seem to have mastered the art of spin, whereby both up and down point in the same direction. This makes you credible how?

We have an economy that runs on cheap oil. The price of oil is now far about the cheap point–$20 barrel or so.

The world cannot produce oil for anything like $20 a barrel any more. That is our fundamental problem.

The cost of production keeps rising. If we want producers to “go after” the expensive to produce oil, oil prices have to be high. But those high prices trip up the economy.

I suppose oil that could be produced for $20 barrel and didn’t produce CO2 would be cause for celebration. But I don’t see it happening any time soon.

Natural gas is now priced slightly less than $20 barrell, based on an energy-equivalency basis. As a rule, the energy-equivalency is perhaps unfair to natural gas, as a BTU of natural gas can generally provide more heat, electricity, work, etc than a BTU of oil (which is a less refined and more impure product).

I’m not really sure why you believe the economy requires cheap oil. The global price of oil has been moderately expensive for almost half a decade, and global GDP has risen quite a bit over this time frame.

Not in developed country’s. Growth has been anemic. It has been high in some undeveloped country’s like India and China, however they rely on coal as their primary energy source which is much cheaper. But the buggaboo is undeveloped country’s rely very heavily on sales of cheap manuf. goods to developed country’s, so when the US & EU go into recession like they did in 08 and now maybe again, those country’s growth drops.

If you think the world can transition from oil to NG, then by all means go for it, however what is touted as a hundred years worth of NG will quickly turn into 10 years if the consumption of that fuel increases 10 fold. But also there is the trillions of dollars needed to convert all of those ICE’s to run on NG. Where’s that going to come from in a financially strained economy?

Is this $20 barrel idea some number you just fabricated? A tremendous amount of Global GDP has been added with oil well above that price.

Perhaps the word “economy” means something special to you, and is divorced from the commonly accepted meaning of the word. So oil hasn’t been cheap for some time, yet global GDP has grown quite a bit – how was the economy not been running, exactly? Because there are scary news headlines? I don’t think we will every cure the problem of scary headlines – we had those with cheap oil.

Oh GDP is growing fine, just ignore those towering trillion dollar deficits. Industrial countries are like a store that makes $50k in sales a month, but borrow $5million a month. It is a great system until you can no longer service the debt. Just look at U.S. debt since 1970, the year U.S. oil production peaked.

Just thought I would leave some charts to go with my comment.

http://tickerforum.org/akcs-www?post=207632

Oil has only been consistently above $20 a barrel for the past 10 years. In that time the global economy has experienced a global financial crisis (2008) and since then many of the major economies have been avoided a recession (on paper at least) by implementing large deficit spending and monetary stimulus. Not only have their been large deficits which make up around 7-8% GDP in the US and the UK but we have also seen interest rates set at one of the lowest rates in over 100 years low not to mention a large amount of quantitative easing. The largest central banks expanded their balance sheets expanded to the tune of $10 trillion since 2008 in attempt to prop the economy up. Without these huge fiscal and monetary interventions it is highly unlikely the world economy would still be growing.

Plus if we consider that much of the economic statistics used by world governments has a optimistic bias due various flaws in how economic statistics are collected then it raises doubts whether the economy is growing at all. For more information on the way statistics such as GDP growth or inflation has this bias please watch the video by Chris Martenson:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zsNgJVD8KgY&feature=autoplay&list=UUD2-QVBQi48RRQTD4Jhxu8w&playnext=2

In any case even ignoring the events of the financial crisis a point that must be borne in mind is that much of our growth in the last 30 years have occurred because the amount of debt has increased faster than incomes. Since GDP measures total expenditures increased debt accumulation AND income is used to determine overall spending however if we remove the debt component (since this practice is not not sustainable) then it is likely the growth in the last 30 years would be far more modest or even negative.

Gail, this is an excellent posting, but leaves me with at last one major question. In 1989 the PIIGS oil, energy and economic peaks and declines were simultaneous. In 1997 oil seems to have led energy and the economy by 21/2 to 3 years. There seems to be something else involved from a “whole systems” POV. In the USA the unsustainable private sector debt increase set the stage (charged the muzzle loader), the Dec 2007 NASB decision to require “mark to market” primed the pan, Bear Sterns cocked the gun, and the oil price spike pulled the trigger. Lehman Bros was the gun firing. The delay from oil price to economy was short because the gun was loaded and cocked. Does oil still have this effect under different economic conditions? The 9 of 10 recessions illustration is pretty unconvincing to me.

There are enough things going on simultaneously, that I don’t think we can expect the same pattern each time. The PIIGS is a group of 5 countries, and Greece is the smallest, so I don’t think it is dominated by its issues. I am afraid I have not followed the details of Europe’s activities (for example, levels of gasoline taxes and carbon taxes) as closely as I might have. I am also less familiar with databases dealing specifically with Europe, so it is not easy for me to figure out an answer.

everything isn’t always about oil: The Euro issues and the banking crisis are related but separate issues in the sense that instead of allowing market forces to strangle public spending and throttle back on sovereign debt, political expediency meant that price shocks were covered by increased debt, so that debt rather than a faltering economy finally became the resource that ran out.

Essentially imagine you have a friendly bank and an overdraft and gasoline gets more expensive: You have tow choices – use less, or borrow more. Nations chose to borropw ore. But that kept gasoline prices high and eventually the worst of all options was exercised: use less AND borrow more.

Then they realised that no one could pay it back.

I agree with you!

Pingback: Lower Oil Prices-Not a Good Sign! | Doomstead Diner

Conservation by Other Means, as Steve from Virginia likes to phrase it on Economic Undertow.

Of course, “Recession” hardly does Justice to what is Coming down the Pipe here.

I will Cross Post this one on the Diner.

RE

http://www.doomsteaddiner.com

John Michael Greer addresses some of the issues in his latest post on The Archdruid Report: The Cussedness of Whole Systems

Yes, the “twilight of the petroleum age” is a problem. We will be seeing it everywhere, I am m afraid.

Dave Cohen on Decline of the Empire has an interesting post about Leonardo Maugeri’s prediction that the world will be swimming in oil over the next few decades and the price will crash creating financial disruption for the industry.

http://www.declineoftheempire.com/2012/06/optimistic-lunatic-says-well-soon-be-swimming-in-oil.html

In the body of the article, he quotes some figures for IEA projections on shale oil and compares them to Maugeri’s and finds Maugeri to be way to optimistic. Maugeri was formerly an oil company executive.

What occurs to me when I read these sorts of things is that the world looks very different for people at different vantage points. Consider:

1. The vantage point of a US Air Force General: If it is physically there, we will just take it.

2. The vantage point of a poor country coming out of dire poverty: A little bit of oil, even if high priced, has a very high value so we will pay what we have to to get it.

3. Relatively poor people in rich countries: It’s all about jobs. Are houses being built? Are roads under construction? Is commerce thriving and creating jobs?

4. Rich people in rich countries: It’s all about financial values. Can the Central Banks and Wall Street continue the Ponzi scheme? Or at least can I secure some real assets and locate them in a safe refuge?

5. Middle class people living in suburbs in rich countries: Will my employer stay in business? Will I have to drive long distances to work with expensive gasoline?

This is really like the blind men and the elephant. It’s not the same elephant for all these different classes of people.

Similarly, in making projections, an oil analyst can come from very different perspectives. Crude oil has been cheaper than bottled water. To an oil executive, this is scandalous because oil is the lifeblood of civilization while bottled water is mostly just a fraud. Or compare it to a soft drink, which is more expensive and a poison. So I think an oil executive will tend to think that ‘if it is there, we will get it’…similar to the Air Force General.

The Engineers tend to look at things like EROEI or gross Net Energy and find that the future is not reassuring.

How it will all actually play out I am not sure.

Don Stewart

Don Stewart

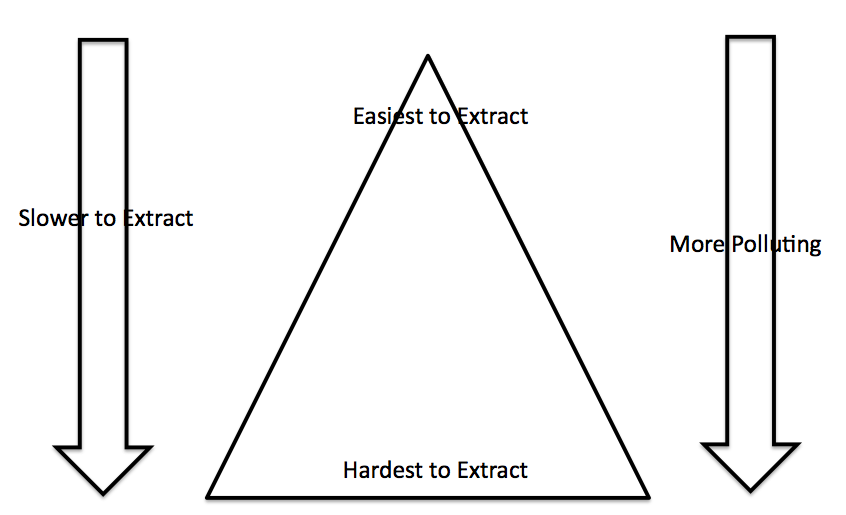

Thanks! I agree. The way I see it is like a big resource triangle. We have lots more oil there, it is just hard to extract, expensive to extract, and slow to extract. There is at least some chance that technology improvements will help make these problems better. It is easy for optimists to focus on these, and the fact that we have in fact, found some improvements (but a lot of that improvement just came with higher price making it cost-effective to do expensive improvements that we have known about for a long time, like steaming out heavy oil). With so much oil apparently available, it is hard to make an iron-clad case that we can’t get to it.

[caption id="attachment_19940" align="aligncenter" width="448" caption="My illustration of impacts of declining resource quality."] [/caption]

[/caption]

thanks for the term ‘whole systems’ analysis rather than ‘holistic’ which I have been using….

And yes, he’s got the basics pegged right down ..good paper.

One of the inevitables is that nuclear power will rise to partially fill the gap in prime energy.

Whole systems analysis reveals that ‘renewable’ energy is essentially unable to fill* that gap. And there is nothing else left.

And that in itself represents a massive transformation of the way things are now. Especially in the realms of transport.

I.e. whilst it is possible to run offices and domestic places, and fixed position industrial production entirely off electricity, that is not the case for a lot of ‘off grid’ primary production – mining and agriculture – and transport of raw materials and finished goods. Shipping is achievable with direct nuclear power, but aircraft and cars are not…neither is it clear how we can economically replace the chemical processes using carbon as a primary reduction agent for oxidated ores, to render them into native metallic elements.

Nonetheless I feel that these are soluble problems. Civilization can continue, severely modified and curtailed especially in terms of population, but not until the broad rush strokes of the ‘new economy’ are sketched out..but the greatest barrier to achieving this, is the presence of the massive inertia of the ‘old economy’ and the vested interests in it.

The most rapid way to whatever the future is going to be, is to stand back, and stop trying to control and rule the world, and simply let the natural human systems get to work ..but the last thing any of the current systems want to do is to euthanase themselves and say ‘we cant fix this: its up to you, . I’ll get my coat…’

In a sense these entrenched systems and vested interests represent the ‘overshoot and partial collapse’ that Gail mentioned earlier..

So I confidentially expect ‘more of the stuff that didn’t fix the problem last time either, but its all we know how to do ‘ …for some time to come..

*For reasons rather technical and detailed and too long to go into here.

Gail:

I see three things at work here:

DEMAND: Recession in the developed world can lead to significant declines in oil consumption because the marginal utility associated with each “last barrel” is relatively small. Do you really need a newer iPod or is your old just still pretty good? This sort of decision process can rapidly scale back oil consumption to the point where you cut things that hurt.

The developing world, however, gets immense marginal benefit for each barrel consumed. You really can use a paved road where none existed before. This situation seems like it should cause each barrel to have a buyer, even if the developed world is scaling back. So why isn’t this happening. Have developed countries cut back too quickly for developing countries to absort the excess? Are there too few developing countries to absorb the excess? Are developing countries also being crushed by recession? This seems important to figure out.

SUPPLY: The monetary cost of new supply is rising, both in terms of EROI (which is insurmountable) and currency units. Falling price will tend to significantly curtail supply development unless there is concensus for future demand. Recession in the developed world both curtails price (due to reduced consumption) and removes any hope of concensus demand.

MONETARY DISRUPTION: The policy response to recession has been monetary easing – a.k.a. printing money – to offset deflationary pressure (falling prices that are so lethal to oil supply). Unfortunately, this policy response has been handled poorly and inflation has primarily impacted financial assets rather than goods and services. As the prices of goods and services stagnate, it becomes harder to absorb high currency prices for energy and the recessionary pressures are redoubled. (I am not advocating support for the inflation-solution, just reading the cards as they seem to have been dealt.)

Ultimately, access to oil is valuable to the economy and some means of developing, delivering, and consuming oil will arise. But, given the feedback mechanisms at work, the ride to the outcome will seem cataclysmically bumpy. And ultimately, we will be significantly weaned off oil by the physics involved.

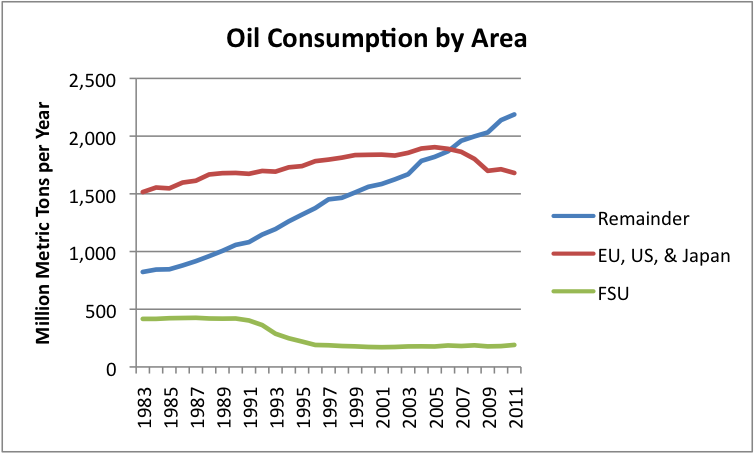

Those are good points. With respect to the question, “Are there too few developing nations to absorb the oil?” I started writing a post about these graphs (plus some others), and I found I hadn’t organized things correctly, so I need to start over. You can sort of guess the answer to the question. (EU is EU-27; FSU is the Former Soviet Union; Remainder is World minus the two other groups.)

[caption id="attachment_28636" align="aligncenter" width="448"] Figure 1. Oil consumption in million metric tons, based on BP’s Statistical Review, shown for the three areas of the world.[/caption]

Figure 1. Oil consumption in million metric tons, based on BP’s Statistical Review, shown for the three areas of the world.[/caption]

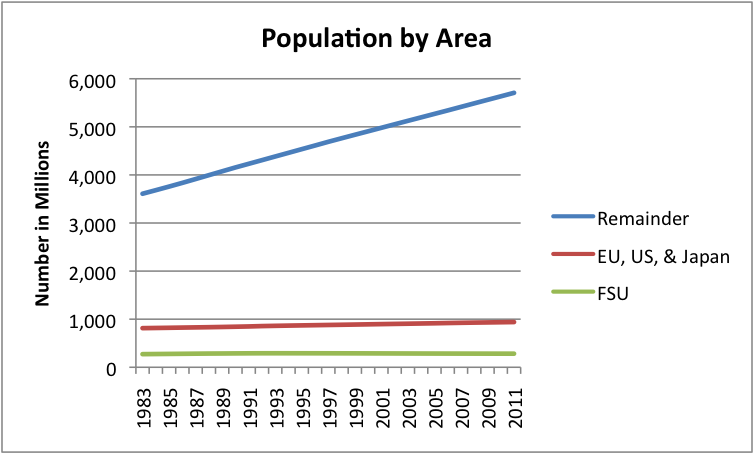

[caption id="attachment_28735" align="aligncenter" width="448"] Figure 2. World population by area, based on data of the US Energy Information Administration.[/caption]

Figure 2. World population by area, based on data of the US Energy Information Administration.[/caption]

Whether or not it’s held to be good, or bad, really depends on what your expectations are.

“The moving finger writes and, having writ, moves on

Nor all thy economics nor ZIRP can lure it back to cancel half a line,

Nor all thy summits wash out a word of it…”

The penalty for living in a real world made of real things that behave in real ways, is that in the end the simple laws of physics demand that society adapts to the limits of production imposed by it.

Classic system analysis shows that with lag in the negative feedback the likely outcome is a peak overshoot followed by a ringing around some level corresponding to a long term maximum.

That ain’t good or bad, that’s how systems behave!

Approximately zero growth is here to stay. After a downturn produced by attempts to restore growth. At least in terms of food and so on. And, like the Red Queen, we may have to run as fast as we can just to stay in the same place.

And finally to finish my troika of quotations, like the Bandar Log, we should maybe reflect on the illogic of Kipling’s monkey people

“We all say it, so it must be true”.

The nearer people in places where decision making is made get to the point of realizing there is nothing to be done, the better, in my book. And if that means a world wide recession/depression/collapse of authority has to happen before people realize these idiots in stuffed shirts simply don’t understand where we are or where we are heading, bring it on.

It is possible to maintain some sort of civilization – but not as long as they are in charge.

Your point on “absolute zero growth” is probably right for the long term. What a lot of people don’t realize is the amount of overshoot that needs to be gotten rid of, before we get down to the level where the absolute zero growth takes place.

Well, I said ‘approximately zero’ – not ‘absolute zero’.. 😉

But your point is valid nonetheless: Those of us who approach things from a physics/system analysis point of view see a simple picture with inevitable general outcomes: Those involved in micro-economic analysis simply don’t see the wood for the trees, and fill in the gaps between with faith.. They are part of the feed-forward that produces more instability.

I don’t see there is much point in trying to change that: After a few years people will realise that having tried every possible alternative, what they finally do will be to hit on the right thing.

Which will probably be to watch the social systems of wealth distribution and the government gravy trains collapse, and blame someone else…as people who are capable of working outside that paradigm quietly get on and construct alternative systems. Probably with copious applications of the venerable AK47…

This is a fine analysis of the demand side of oil. But on the supply side, a collapse in oil prices could mean not only oil companies going bankrupt but even entire oil-exporting nations going into turmoil. All that wonderful extra capacity is predicated on high oil prices. Much below $80 a barrel it doesn’t make economic sense to eke oil out of tar sands or shale.

That is a good point. I perhaps should add a paragraph or two. Collapsing prices of oil cause problems of many sorts.

Note: I added a section–“If Oil Prices Stay Down, or Drop Further, Not All Oil is Economic”.