The usual assumption that economists, financial planners, and actuaries make is that future real GDP growth can be expected to be fairly similar to the average past growth rate for some historical time period. This assumption can take a number of forms–how much a portfolio can be expected to yield in a future period, or how high real (that is, net of inflation considerations) interest rates can be expected to be in the future, or what percentage of GDP the government of a country can safely borrow.

But what if this assumption is wrong, and expected growth in real GDP is really declining over time? Then pension funding estimates will prove to be too low, amounts financial planners are telling their clients that invested funds can expect to build to will be too high, and estimates of the amounts that governments of countries can safely borrow will be too high. Other statements may be off as well–such as how much it will cost to mitigate climate change, as a percentage of GDP–since these estimates too depend on GDP growth assumptions.

If we graph historical data, there is significant evidence that growth rates in real GDP are gradually decreasing. In Europe and the United States, expected GDP growth rates appear to be trending toward expected contraction, rather than growth. This could be evidence of Limits to Growth, of the type described in the 1972 book by that name, by Meadows et al.

Figure 1. World Real GDP, with fitted exponential trend lines for selected time periods. World Real GDP from USDA Economic Research Service. Fitted periods are 1969-1973, 1975-1979, 1983-1990, 1993-2007, and 2007-2011.

Trend lines in Figure 1 were fitted to time periods based on oil supply growth patterns (described later in this post), because limited oil supply seems to be one critical factor in real GDP growth. It is important to note that over time, each fitted trend line shows less growth. For example, the earliest fitted period shows average growth of 4.7% per year, and the most recent fitted period shows 1.3% average growth.

In this post we will examine evidence regarding declining economic growth and discuss additional reasons why such a long-term decline in real GDP might be expected.

Connection of GDP Growth with Oil Supply Growth

It should not be surprising to find that there is a close tie between GDP growth and oil supply growth. Oil is used in many ways, from the manufacture of goods (synthetic cloth, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, asphalt for roads), to transport of goods and people, to food production (plowing, harvesting, weed killers, diesel irrigation), to operating construction equipment, to mining. While it is possible to substitute away from oil in some situations, or to find more efficient ways of using the oil, we have literally trillions of dollars of machinery in the world that uses oil right now. Because of this, the rate of substitution away from oil is necessarily very slow.

James Hamilton has shown that in the United States, 10 out of 11 post-World War II recessions were associated with oil price spikes. He has also published a paper specifically linking the recession of 2007-2008 with stagnating world oil production and the resulting spike in oil prices. I wrote an academic paper, Oil Supply Limits and the Continuing Financial Crisis, explaining some of the connections I see involved.

One connection between oil supply and the economy is the fact that when oil prices rise, indicating short supply, salaries don’t rise at the same time. Fuel for commuting and food (which is grown and transported using oil) are necessities, and their prices tend to rise as oil prices rise. Consumers cut back on buying discretionary goods and services, so as to have enough money for these necessities. This leads to people being laid off from work in “discretionary” industries, and a whole host of other effects we associate with recession.

Figure 2, below, shows world oil supply (broadly defined, including biofuels) with trend lines fitted to periods exhibiting similar growth patterns. It is these same time periods that I fit trend lines to in Figure 1, with one small exception. I had consistent real GDP data going back only to 1969, so stopped at 1969 rather than 1965 with GDP.

Figure 2. World oil supply with exponential trend lines fitted by author. Oil consumption data from BP 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy.

What we see in Figure 2 is a pattern of falling growth rates in oil supply rates, similar to the declining pattern we saw for real GDP in Figure 1. In Figure 2, the growth in oil supply falls from 7.8% per year in the first fitted period, to 0.4% per year in the last fitted period. The “gaps” that I didn’t fit lines to were periods of falling oil consumption. A glance up at Figure 1 shows that these periods where no line was fit (that is, the places where the black “actual” data shows through on Figure 1) correspond to relatively flat GDP periods–as a person would expect, if high prices/short supply are associated with recession.

A person wouldn’t expect the two types of growth rates (oil supply and real GDP growth) to be exactly the same. The GDP growth rate would likely be higher than the oil growth rate because the oil growth rate is theoretically depressed for several reasons: continued switching from oil to cheaper fuel (often electricity); improvements in energy efficiency; and a gradual change to more of a service economy. (Services use less energy per unit of GDP than the manufacturing of goods.)

If we compare the two fitted growth rates (world oil consumption and world real GDP), this is what the comparison looks like:

Figure 3. World Oil Supply Growth vs Growth in World GDP, based on exponential trend lines fitted to values for selected groups of years. World GDP based on USDA Economic Research Service data. Earliest time-period uses 1969 to 1973 for both oil and GDP for consistency.

Downtrend in Real GDP May Be Understated

The last thing governments want to do is to let their constituents know that the economy is currently doing less well than in the past. There are (at least) two ways that governments can increase real GDP:

1. Understate their inflation estimates. The way “real GDP” is calculated involves first figuring GDP based on how much goods and services increased during the period in question, and then “backing out” the amount of the GDP increase that was due to inflation. There is latitude in figuring out how much inflation to reflect. For example, in the early years, my understanding is that if the price of beef went up, it directly affected the calculation of the inflation rate; now, there is an implicit assumption that they buyer will be willing substitute chicken to some extent instead, keeping the inflation assumption lower and the real GDP increase (as calculated) higher. There are many other things that be manipulated as well–for example, how the cost of housing goes into the calculation. The site Shadowstats gives one view of how changes since 1983 distort reported US real GDP amounts.

2. Encourage lots of additional debt. Real GDP looks at the amount of goods and services are produced and sold, not how they are paid for. If the government sponsors a program to provide mortgages to people who have no chance of ever paying them back, and this results in the sale of more houses, this will help real GDP–at least until the borrowers start defaulting on their loans. Increases in other types of loans work to increase real GDP too, including auto loans, student loans, and government debt.

Besides increasing real GDP, increasing debt also acts to increase employment, since it takes workers to build the things that people who get the loans can now afford. In other worlds, the higher loan amounts increase employment of people who build new cars or new houses, or who teach at universities.

The problem with encouraging additional debt is that it at some point the amount of debt becomes too much for holders of the debt to service, and they start cutting back on other purchases. For example, recent graduates with a lot of debt are likely not to be in the market for new homes unless they have very high-paying jobs. So, at some point, additional debt becomes self-defeating, especially when the economy is not growing very quickly. Too much debt seems to be one of the limits, besides oil limits, we are reaching now.

Other Factors Holding Down Real GDP Growth

We live in a finite world, and this fact imposes limits. The amount of land suitable for cultivation is not expanding over time. There is limited fresh water for irrigation and other uses. In many areas, water tables are dropping. Ores are declining in quality because the highest quality ore tends to be extracted first.

Pollution, including carbon dioxide pollution, leads to attempted substitution by higher cost alternatives. It also leads to the addition of devices such as expensive filters. Both of these add costs, without increasing the amount of usable goods and services (in the usual definition) produced. Peoples’ funds for discretionary goods can be expected to drop as a result, (since funding through taxes or other approaches is mandatory) putting downward pressure on real GDP growth.

There is also the issue of how many new entrants are added to the paid labor force. If, for example, in the early years, many homemakers are being added to the paid labor force, their addition will tend to raise GDP growth, because the goods or services the homemaker creates will be added to real GDP, as well as the cost of daycare for her children, if this is purchased. Once homemakers have been pretty well absorbed into the labor force, that positive influence on real GDP will disappear. If the number of people employed starts declining (because of more retirees, or because people can’t find jobs), or fails to rise as quickly, this will tend to slow economic growth.

Oil Importers are Likely to Have Lower Economic Growth than Others

There are a couple of reasons why oil importers can be expected to have lower economic growth than other countries, especially when oil prices are high. First, oil importers have the problem of needing to pay exporters for crude oil or oil products. The revenue that is spent on higher priced crude oil could have been spent on discretionary expenditures. It is unlikely that the oil exporters will reinvest the money in the economy of the buyer of its oil–they are just as likely to reinvest it in their own country.

The second reason is that oil importers tend to be the countries like the United States and Europe that “developed their economies” early on. Since these countries have hired women in large numbers since World War II, most homemakers who want jobs already have them. If birth rates have slowed, these countries may be seeing disproportionate growth in the retiree population and fewer workers in ages where employment usually takes place.

In the United States, if we do curve fitting (of the type shown in Figures 1 and 2) to the reported number of non-farm workers employed in the United States (from the Bureau of Labor Statistics), and compare these employment trend rates with the corresponding trend rate in US GDP growth, we find a high correlation:

Figure 4. US growth in number of non-farm workers versus growth in real GDP. US real GDP from US Bureau of Economic Activity; Non-Farm Employment from US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fitted periods are 1969-1973, 1975-1979, 1983-1990, 1993-2007, and 2007-2011.

Note that decreased growth in the number of employees could be taking place for any number of reasons–less growth in illegal immigrants, fewer homemakers going back to work, more people going to college, or more people retiring or taking disability coverage, or just generally discouraged.

It is my observation that the number of workers in the US today seems to depend on the number of jobs available. If jobs in some fields are being increasingly shipped to lower-cost countries–the ones we will see in Figure 7 are now using a disproportionate share of the world’s oil–these jobs will not be available, no matter how many workers might be willing to take them, if they were available.

If we look at the trend in real GDP growth for three major areas (United States, European Union-27, and Remainder = World minus the US and EU-27) , we discover that indeed, all three of the areas show a downward trend in real GDP over time (Figure 4, above). The GDP growth of the EU-27 and the US start from a lower level, and drop off more in the 2007-2011 period, (when the price of oil imports was more of an issue) than the “Remainder” grouping.

Figure 5. Annual growth in world oil supply compared to annual growth in real GDP, both based on exponential trend fits to values for selected years. Oil supply data from BP oil consumption data in 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy; real GDP from USDA Economic Research Service.

One reason why the Remainder-GDP may be doing better than the others is that heavy manufacturing, and the jobs that go with heavy manufacturing, are finding their way to lower cost countries. High oil prices may also be discouraging oil importers from purchasing oil. If we look at oil consumption for the three groups, this is what we see:

Figure 6. Comparison of oil consumption by area (United States, European Union -27, and rest of the world), based on BP’s 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy

Much of heavy manufacturing has been moved out of the United States and the European Union. Figure 7 below shows that the rest of the world is now using well over half of the world’s oil:

Figure 7. Percentage shares of world oil consumption based on BP’s 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy.

Going Forward

We have seen (Figure 5, above) that all three grouping shown (United States, EU-27, and the rest of the world) are showing declining real GDP patterns, similar to the world pattern. GDP growth rates of the United States and EU-27 are both at lower levels than the World and Remainder, for reasons explained.

It is hard to see why current trends wouldn’t continue, with growth in real GDP continuing to decrease for all three groups. Regardless of the hoopla in the United States press about supposed growth in oil supply, the fact remains that growth in world oil supply has been worrisome for many for roughly 40 years, since US oil production started decreasing in 1970. It is hard to believe that the latest “fix” is going to turn things around. The typical pattern in oil supply is for extraction in an area to hit a maximum (or perhaps a plateau) and then decline.

Figure 8. Crude oil production in the US 48 states (excluding Alaska and Federal Offshore), Canada, and Europe, based on data of the US Energy Information Administration.

Figure 8 shows (among other things) how steep the US drop in oil production in the contiguous 48 states was starting in 1970. This decline set the stage for the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo, since oil-producing countries now had the upper hand. Production in Alaska and in the Gulf of Mexico eventually helped offset part of the drop, but the Alaska production (not shown) is now declining as well. Change in the balance of power regarding oil production following the decline in US production, and recognition that increased imports would cause balance of payments problems, seem to have influenced the US and Europe’s decision to focus on service industries and on industries with little oil usage, holding their oil usage down (Figure 6).

Figure 8 also shows how new onshore techniques–fracking and other enhanced oil recovery–are affecting US crude oil production. While US-48 states crude oil production has shown a 25% increase since 2006, this production is still only 39% of the 1970 amount, and about equal to 1942 production. Oil production in Canada (which includes the oil sands) is rising, but not very rapidly, from a low base. It is hard for small increases such as those of Canada and the US-48 to make up for major declines in production occurring in Europe and elsewhere. World oil supply would be increasing by more than a fraction of 1% per year if changes frequently noted in the US press were really making an important difference in world supply.

If growth in world oil supply is constrained and may possibly begin to fall in total in not too many years, this adds to the downward pressure on world GDP growth for all of the areas of the world. Thus, re-examination of GDP growth assumptions seems to be in order. Perhaps slow recent growth is not an aberration–perhaps future real GDP growth will be even lower.

They key to all of this is not the actual resource constraints itself … it is the combined constraints and increased costs that will destabilize the world quite rapidly once we hit an unknown tipping point brought about by combined constraints, financial crisis and political turmoil. We have for some time now been experiencing extreme “pre-shock” events in the markets which hint of the much larger underlying problems being buried by complex financial instruments in all corners of the globe. The machine of consumerism will be pushed to continue at all costs to support this debt and allow for more expansion …. no one wants to do the math …. there clearly isn’t supply available for a doubling of demand in any critical commodity ….. our governments and financial systems are not designed for this inevitability

US wine–I agree. Everything is being hidden for now. The question is how long it can stay hidden. Available resources keep going down as world population goes up.

Pingback: Vancouver Peak Oil » Evidence that Oil Limits are Leading to Limits to GDP Growth

Pingback: What Level of Oil Supply Growth is Needed to Support World GDP Growth? | RefineryNews.com

Pingback: What Level of Oil Supply Growth is Needed to Support World GDP Growth? « Last Chance For Freedom

Pingback: How much oil growth do we need to support world GDP growth? | Our Finite World

It’s funny how people like Micheal Levi and the New America Foundation are seeing a completely different future.

http://blogs.cfr.org/levi/2012/07/13/the-new-old-world-of-u-s-oil-policy/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+mlevi+%28Michael+Levi%3A+Energy%2C+Security%2C+and+Climate%29

The New America Foundation is hardly some Koch Brothers think-tank. It’s current president is the former editor of the Washington Post.

From the article: “If the new narrative turns out to be true…” Note the prominence of the “If”. I suppose that if the new narrative that every Tom, Dick, and Harry energy “expert” like Levi did prove to be true everything else he concludes might also turn out to be true. But the problem is that the if is a really big if.

I notice in Levi’s list of expertise he did not include his doctorate in physics. On the other hand, had he actually taken any physics he probably wouldn’t have written this article.

Levi’s pretty smart. I have a masters in physics, one of my classmates switched to geosciences and is working on the oil sands in Canada. Levi’s descriptions of the pros and cons of what’s happening there have been absolutely spot-on, he is almost the only writer/blogger getting the tar sands story correct.

I’d be pretty surprised if he’s 100% backwards on fracking and shale as well. He seems to listen carefully to real scientists and present a very accurate view of consensus science.

If Levi’s all wrong here then nearly everyone in geoscience is all wrong as well – he’s not staking an outlier position here.

Your response is puzzling. Levi’s article seemed to be implying that the new narrative was about how we are increasing oil production and so all of the old worries about limits (or at least impending peak production) were now moot. And he seemed to be implying that that was reality. Hence my questioning his background (not his supposed smarts).

That “new” narrative is certainly out there making the rounds and turning a lot of heads. But that narrative conveniently forgets one very important point that realists recognize as problematic, and that is EROI. Having a masters in physics I would assume you understand that all of these new sources of oil and oil-like hydrocarbons require more energy to extract and refine. The technology might make it more feasible to do the extraction but not necessarily lower the energy costs to do so. Gail can quote the evidence, which shows that this supposed flush of new oil is not producing the net gain in exergy that is actually needed in order to really change the narrative. Hence I reemphasize that the use of the word “If” is totally apropos.

Well, I doubt all these fracking companies are getting a negative energy return on investment.

I’m not sure people fully understand what the EROI is for fracking shale (particularly if you include all the oil and gas) … but there is no doubt that the EROI for shale has dropped considerably over the last decade.

Maybe if we didn’t have all our debt, we had started these new oil techniques 10 or 20 years ago, and they had caught on around the world as well, would Michael Levi have a chance of being correct. Its too little, way to late, as far as I can see. It will help the incomes of some US citizens, and it will help the revenue of some states, but it is not enough (in the 6 moth timeframe needed) to fix world problems, or even USA problems.

Well, I don’t think Mr. Levi thinks shale oil will fix everyone’s problems. We can all agree, there are problems now, and in the future, there will still be problems.

But The New America Foundation’s predictions (which Levi is essentially just reporting) is that the US and Canada are entering a phase not that dissimilar from the late 40s and early 50s – high debt, but also a growing economic engine powered by domestic fuel.

Are you really predicting a catastrophe within 6 months? So we should check back in Feb 2013 or so and see if all the cars have stopped running by then. That seems far fetched in the extreme,

Pingback: Evidence that Oil Limits are Leading to Declining Economic Growth | The Great Transition | Scoop.it

Pingback: Evidence that Oil Limits are Leading to Declining Economic Growth »

Hi Gail, I wanted to post a link to a great new paper,

Financial System Supply-Chain Cross-Contagion:

a study in global systemic collapse.

http://www.feasta.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Trade-Off1.pdf

Well worth the read everyone.

Yes. I know Dave Korowicz and think a lot of his analyses.

Gail, I am glad to know you are aware of David Korowicz’s work. I posted the link as I hoped it would be encouraging to see others analysis that support your own; if only because the implications of your analysis paints a dire picture for the status quo. That tends to make certain people defensive and even angry when reading your work I would guess; I thought some very well thought out analysis that is in agreement might be a nice change.

I believe that the current plateau of crude oil has essentially ended real economic growth. I was glad you linked your previous post entitled “The Link Between Peak Oil and Peak Debt” as this point is essential to understanding the current situation industrial civilization finds itself in today. If one ignores the debts of the industrialized countries it is much easier to make the argument that everything is fine.

Running completely out of oil or even starting the decline in global production is not the most pressing problem I see, it is having enough cheap energy to run the growth based industrial economies. I think we passed the point of having enough cheap energy to fuel growth when peak oil per capita hit around 1979. The name of the game has been diminishing returns across the board since then. Debt and seemingly endless credit keeping reality from announcing the end of the waste based industrial system. Reality will come knocking again however, it always does.

Pingback: Why are oil prices going wild? » Peak Oil Tasmania

Gail,

I read your excellent material whenever I get the opportunity though I have to admit I do not yet have a full handle on the technical detail.

There is increasing momentum around the argument that fracking is going to do for petroleum what it has done for natural gas – ie: create much greater production – including domestic sources – and that the price of oil will fall (George Monbiot begin among the most recent to make that argument after previously arguing that peak oil was imminent.)

It does seem that fracking has changed the game in NG.

What’s your sense of this?

Thank you for your excellent work.

-Rafael

I think George Monbiot is deceived.

The “game changing” aspect of natural gas has to do with not being able to match supply with demand. The reason the price is so low is because there is far more supply than demand. Sellers who are fracking to get dry natural gas can’t possibly make money at the price natural gas is selling for. So there has to be a reduction in supply and/or higher price. Recently natural gas drilling is being cutting back. There are allegations that Chesapeake has overstated its reserves. We will have to wait and see how this shakes out. We need “Fracked” gas just to offset declines in cheaper-to-produce natural gas. The gas rig count is down 44% since last October, according to Baker Hughes. We may have some more gas, at a higher price, but don’t count on being able to run huge numbers of vehicles on it.

With respect to oil (and gas with lots of “liquids”), there is at least a chance that the “fracking” is not so expensive as to be a problem, because the product extracted (oil and natural gas liquids) is more expensive to begin with. But there is a big difference between being able to raise US production a little, and being able to offset big declines in oil production of other types around the world. What the world needs to solve its economic problems (but not its carbon dioxide problems) is a large supply of cheap oil. Fracked oil can’t be very cheap, because of the high front-end costs, high decline rates, and small size of individual wells. Fracked oil can perhaps work if the price of oil can stay high. It can help the US economy, but it won’t even solve the US oil import problem, much less the world oil supply problem, in my view.

So you think the break even point for fracked oil is where, exactly? I’ve read lots of people saying it is in $60-$70 range at this point, and dropping as the technology improves.

I agree that isn’t cheap oil, but it’s not expensive oil. So the Monboit argument is that the world has a large supply of “neither cheap nor expensive” oil.

Certainly in the US fracking has offset the declines from traditional drilling. You are seeing this trick cannot be repeated around the globe? Is the US very unusual with re to shales? I think there are many in Canada, Argentina, Australia, even Europe… no?

I think it is less useful to talk about what can be done with ZERO fossil fuels, than it is to talk about what can be done with severely reduced fossil fuels, in the near future. Obviously, not much can be done with zero fossil fuels, as that imposes a strict constraint on economic activity. However, there will be non-zero and indeed non-negligible fossil fuel reserves for at least the next 100 years avaliable at positive EROI. I believe that in a shortage, non-essential uses like oil based transport (freight trains can run on coal or electricity produced from nuclear/gas/hydro/coal) can be cut severely and the oil reserved for high value added (converting to durable product) uses like chemical feedstocks.

Transportation liquids is only a big deal in countries without a very efficient rail network and public transport but have high levels of economic development that require fast transport. Africans won’t notice because their economic activity does not rely on fast motorized transport. East Asians and Western Europeans in France and Germany will notice less because their non-export economic activities are supported by a strong national rail network in high population density areas and cultural preferences for public transport.

Indeed, in situations with reduced but non-zero and non-negligible fossil fuels, there’s many countries that are much better poised to handle the situation than one that must continuously consume liquids to fuel both personal and commercial transport. Countries in which electricity and coal based public transport is not financially feasible will grow less competitive in such a situation.

Even in farming, some countries use mechanization much less than others. In Asian, some Latin American and Western European countries, physical labor is a much greater component of farming due to small plots of very high yield fertile soils irrigated by rain and rivers, (as opposed to huge plots of low yield soils that must be continuously irrigated by mechanical pumps). Mechanized farming is only big in a few areas of the world growing huge amounts of dry staples like corn and especially soybean. Soybean and corn production also goes mostly towards chemical and animal feedstock, so any decrease in their production should show up mostly as increased meat prices and reduced sugar content, not as human suffering.

You and I see things fairly differently.

To me, the amount of reserves that can theoretically be extracted at positive EROI is totally irrelevant. What is relevant is how long the economy can hold together in its current form–with adequate long distance trade, and manufacturing of high tech goods, and people traveling around the world to do such things as consult on oil well problems. The continued existence of our current banking system is important as well.

Once things start “unravelling” to that point, it seems to me that we will lose most of our high tech uses of fuel. In fact, we will lose everything that requires high-tech equipment for repairs, unless somehow we are able to make those repairs with local equipment. Thus I expect we will start losing electricity, for lack of spare parts. Also, we will find it difficult to reconnect homes and businesses after storms. We will start losing some of current hydroelectric, it repairs can’t be made. We will lose the wind turbines quite quickly, because of their frequent need for repairs. We will lose most oil and natural gas, except that wells that are currently producing will continue to produce. I would expect a steep drop-off in drilling of new wells, as parts become difficult to obtain and specialized expertise becomes hard to come by. New computers will likely not be built, for example, so that as old ones die, there will be no replacements.

Some coal production may continue, if it can be done in a low tech manner (as Heading Out has written about on The Oil Drum). It won’t be shipped far, though, unless suitable low-tech transportation for the coal is available–barges, or trains using coal for operation. Unless electric wires are available, the coal will to a significant extent be used directly for heat, rather than electricity.

While we may have been able to do a lot of things with coal alone, say in 1900, we don’t have equipment sitting around now that is adapted to coal use, so it will be less useful to us today. Perhaps we with time can raise horses to provide transportation, and build coal-fired steam engines, but we don’t have them now available. Thus, transition back to what we did in an earlier period will not be easy to do.

Electric trains are already widespread in most developed countries and developing manufacturing economies. Diesel trains are mostly used in Canada, US and Australia as well as developing extractive economies without good electrical infrastructure. There’s no need to go back to direct use of coal for countries that already have electric trains.

The amount of oil that goes into maintaining the electrical grid is tiny compared to other uses that can be called frivolous. If anything, strong governments around the world will enforce rationing of fuel and force the grid to stay up, because the grid is one of the few things that simply cannot go down without a slide down even further, and if things slide, the elite lose, and they don’t want to lose. And they can; the grid takes up something like 5% of the oil we use. Lets say that producing resources in general takes up 20% in the future – that’s not too bad, considering today’s EROI is 15:1 for conventional oil and 3:1 in the tiny amounts of shale oil. They can survive with a decline by simply choking off half of supply for the masses and redirect all the oil to maintaining the grid and the military.

This is very possible. Look at North Korea. In the 60’s and 70’s, North Korea wasn’t that bad! Its economy was growing faster than South Korea’s, it was a food exporter, and it was more free than the dictatorship down south of General Park Chung Hee. Well in the 1990s it lost its main supplier of fertilizer, oil and parts, so it turned out that North Korean elites had 2 choices: lose power, or change. They changed – they turned the government into a hereditary monarchy and gave 25% of the budget to the military to enforce rationing. Almost all oil in North Korea today is prioritized to the military and the people went from riding buses to biking and riding donkeys.

I don’t think it will be a fast decline. I think it will be a “long emergency” as long as the ability to coercively redistribute and limit energy is there, because a fast decline is against the interests of the elites. If they have the ability to redistribute and keep the system propped up longer.

My question is about government’s ability /willingness to do rationing.

One concern is that if things get as bad as to need rationing, there will be huge governmental changes. Not only will elected officials be “out the door”, but there are likely to be take-overs by non=-elected officials. In some cases, countries will fracture into smaller pieces, in the way of USSR or Yugoslavia.

It seems to me that one of the big areas for a slide downhill has to do with repair (or lack thereof) after a storm. It is expensive and requires oil to get crews in to clean up after a storm. As the government suffers from worse and worse funding, it will not be able to help with disaster relief as much as in the past. Insurance companies cover insured damage, but typically this is wind but not water, and may have big deductibles. Infrastructure such as roads that get washed out will not be covered at all. One of the big areas for decline in electrical service may then be storm damage that never gets repaired.

“Oil Importers are Likely to Have Lower Economic Growth than Others” –

You said it!

Without sufficient economic growth, interest can’t be paid. Unless lenders are willing to forgo their profits, loans go bust (it seems maybe some of them are willing to do this temporarily, sometimes).

Without profits, the Banking system as we know it will evaporate. Without the ability to ‘borrow’ resources from the future, growth can’t happen (back where we started – the limits to growth).

It’s called a death spiral.

And that’s the reason why:

“The last thing governments want to do is to let their constituents know that the economy is currently doing less well than in the past. ”

This is a great post, and I really appreciate the forum you provide as well. Some of the most interesting parts show up in the comments, and your reponses to them.

Pingback: Plan for lower growth in real GDP going forward »

This really is a ripper of a post Gail. Enough said.

Wouldn’t a better Title be “Prepare for CONTRACTION of Real GDP going forward”?

Although we might slow for a while and perhaps plateau, the trendline if followed would see GDP NEGATIVE by around 2015 the latest.

Anyhow, despite the Namby-Pamby Title, the usual great graphs and analysis. I reposted it on the Diner Blog at:

http://www.doomsteaddiner.org/blog/2012/07/14/plan-for-lower-growth-in-real-gdp-going-forward/

RE

http://www.doomsteaddiner.com

Pingback: Plan for lower growth in real GDP going forward | Doomstead Diner

Wouldn’t a better Title be “Prepare for CONTRACTION of Real GDP Going Forward”?

We might see slowing of growth and a short plateau for a while, but overall a SHRINKAGE is what is most likely to occur, not just a “Slowing of Growth”.

In any event, despite the namby-pamby title, the usual great research and charts Gail. I will cross post this one on the Diner Blog.

RE

http://www.doomsteaddiner.org

Other sites will have my article up under different names. I see Business Insider has it listed as The World has Entered a Permanent Decline in Growth. I see Forespros.com has it on its front page under the title, “Real GDP: Plan for Lower Growth“. Financial Sense uses the original title.

The problem a person has, is that readers will write an author as a nut, if they say something too “over the top”. Sites that copy my post will pick more or less inflammatory titles, depending on their orientation.

Academic articles tend to by titled with a title that understates the significance of the article somewhat. I tend to go a little in that direction–give the reader the impression I am careful about what I say, and don’t run around saying, “The house is on fire,” if only the kitchen is on fire, and there is a reasonable chance it will spread.

By the way, if you cross post the article, you are welcome to pick a different title, as others do.

I always maintain as much fidelity as I can to the Original Article the Author put up along with full linkbacks. I’m an ABSOLUTE NUT about Propaganda, Free Speech and Censorship issues, which includes Spinning an Author’s work by messing with their Titling. The only time stuff appears at all different on the Diner Blog than the original is because of formatting issues sometimes. Not a problem with yours though because you also run the same WP software.

I do grasp your methodology, you don’t want to be marginalized as a Nut Case Cassandra, and you consider the MSM outlets like BI etc. to be an important place to publish your material. Problem with that methodology is that it all gets Whitewashed to make it palatable to the Average Academic,and it all digests as PABLUM.. There isno real Call to Action when youwrite this way.The whole POINT of the Blogosphere IMHO is to STOP the whitewashing and tell it like it IS.JMHO there.

Oh,also,you can delete the Repeat Post I made.on this one. It did not appear to take the first time.

RE

http://www.doomsteaddiner.org

I did change the title, but I am not sure this is much better. It now says, “Evidence that Oil Limits are Leading to Declining Economic Growth.” Hopefully a person can get to it either way.

That is to my editorial eye at least a little more accurate. I’ll change the Title on the Diner also to match. That won’t change the Permalink though unfortunately.

Anyhow, keep up the good work writing to make your stuff palatable to Business Insider. I’ll hold up my end fighting the Gonzo Guerrilla War on the Blogosphere 🙂

RE

http://www.doomsteaddiner.org

Business Insider is now subscribing to my RSS feed, and says they are “fully syndicating my site”. I expect that they will still skip some posts, though.

Oil Voice which I believe is a big European site is now carrying some of my posts. I see this article is featured on its front page today.

I think I mentioned Forexpros and Financial Sense before.

All these sites found me, rather my finding them. If you know of other sites I should be seeking out, let me know.

Don

I mentioned roadside grass trimming in Britain as an indicator of affluent normality – diesel, local tax spent on ‘priorities’. Personally, the tidy minds and the priorities of the ‘motorist’ mentality scare me. But it indicates we are still funded, up to a point, to live in la-la land.

I agree about habitats.

Phil

I would like to suggest the following line of thought. It is primarily in response to Question Everything (which I always enjoy reading) and the comments about Britain. This comment will probably sound catty, but I say it with sincerity.

The energy captured by photosynthesis is five times that delivered by fossil fuels. So, how do we measure the decline or advance of societies?

A. We can look at the deterioration brought about by declining availability of fossil fuels. E.g., is the grass neatly mowed? Is welfare still available?

or

B. We can look at how well the society is doing in terms of harvesting solar power to increase biological activity and therefore increase the yield from photosynthesis. (The Permaculture perspective)

If we take the B perspective, we will ask if the society has figured out that mowing grass if usually a stupid thing to do. For example, all natural agriculture depends upon the health of the ecosystem and the health of the ecosystem is dependent on beneficial soil creatures and insects and birds and animals. Our local Agricultural college advises farmers:

Ugly is OK. Neatly mowed areas offer few resources to beneficial insects or wildlife, while areas that look unkempt to us may be great habitat for wildlife…Farm Ugly to enhance wildlife populations. For example, fallow field borders are basically weedy strips that are lightly disked roughly every 3 years to keep out woody vegetation…When you understand that neatness doesn’t equate to habitat and appreciate the value of lightly managed vegetation, then areas that are biologically productive will begin to look attractive.

Similarly, we might inquire if the society is empowering the poor:

Does this society make it easy for poor people to grow their own food and build their own shelter and capture their own water and provide necessary fuel?

If we look at what Western societies are actually doing, we find that they are destroying habitats and making life exceedingly difficult for poor people to stand on their own two feet.

Don Stewart

I agree that Western cultures are destroying habitats and making it difficult for poor people to stand on their own feet, and that mowing lawns is counter-productive.

There are a lot of other animals (including insects) that would like to eat the products of photosynthesis. We can perhaps select plants so there are more plants of the type that are “food” in the mix, but over time, I think the portion that goes to insects and animals is likely to increase, if we stop using fences (other than the simplest), pesticides, herbicides, etc. So I am not as optimistic about increasing the products of photosynthesis that humans actually consume.

Gail

My personal experience shows me that a healthy, diverse ecosystem carries a lot more predators. Since I made the change in my own yard, I have far more wasps and lady beetles and small lizards and a whole host of other predators. That is exactly what Permaculture teaches, and what the Professor from the Agricultural college was talking about. He was showing and telling about a plot which he had planted on the farm of a friend of mine. Just across the fence was a wide strip of land which bordered a paved road. That strip of land could have been planted in an ecosystem friendly fashion rather than being mowed regularly. If you take a look at Teaming with Microbes by Jeff Lowenfels and Wayne Lewis, or Garden Farming for Town and Country by Peter Banes, I think you will become convinced that all the pesticides and herbicides and synthetic fertilizers are simply a dead end. They kill the ecosystem and make the crops vastly more susceptible to disease and encourage soil erosion and produce less nutrient density for human consumption–as well as fostering utter reliance on an imperiled industrial system.

I understand your reluctance. But if you don’t give the alternative a fair hearing, then you must pretty much resign yourself to despair as you contemplate the collapse of it all.

Don Stewart

Don Stewart

I think Permaculture can do something. I don’t think it can feed 7 billion people. I am not quite sure where in between it really falls.

If humans had spent 98% of their time on earth doing Permaculture, I would be convinced.

Gail

I suggest that you compare this video of a recent interview in Calgary with Toby Hemenway

http://www.patternliteracy.com/videos/verge-permaculture-interview

with Dmitry Orlov’s current blog review of the book

Unlearn, Rewild

I would summarize by saying that both men are intrigued by the potential for a ‘de-civilization’ movement. I would also suggest that what they are talking about is, indeed, exactly what humans have spent 98 percent of their time on earth doing.

Toby is writing a new book on ‘what we need to do with civilization’. I am not an insider on that and so don’t know exactly what he is thinking. He has given a couple of talks in California, but I am far away in North Carolina and so don’t know what he is thinking. As for Dmitry, he always makes perfect sense but is seldom predictable. But the evidence indicates that both are thinking about a world which is, indeed, much more attuned to our heritage.

As for feeding 7 billion people. I sort of doubt that either man sees that as a priority. My own views on the subject are conflicted. But it is very clear to me that humans need to be in the environment they evolved to live in. And that is not the world of LIBOR scandals and Jaime Dimon’s manipulation of derivatives.

My tentative conclusion is that Peter Bane offers the safe and sane alternative. The Garden Farmer never has to wonder what he should do next–his garden always tells him. There is a certain satisfaction in having your life so well mapped out (of course…marriage is another possibility and then your wife tells you what to do.)

Don Stewart

Pingback: What kind of species are we? | Knowing what we know now . . .

Those second-derivative graphs leave no doubt which pedal the foot is on.

Actuaries have “grown up” with different ways of looking at data than economists. Economists seem to be focused on building models looking at the short term, and the results of many (relatively small) countries. Actuaries start with huge amounts of “non-credible” data. So the task is one of “teasing-out” trends and other useful information, when to the casual observer, all there is, is a bunch of noise. We tend to start with the biggest pieces, and work downward to smaller “less-credible” pieces. We also don’t have a preconceived notion as to what the “answer” is. We don’t have some hallowed actuary who has said, “Things can always be expected to follow such and such pattern.” So that leaves the door open to approaches that are simple, but which economists seem to miss.

Gail

Your charts become more and more compelling!

I personally have struggled with ‘the shape of things to come’ since 2005. I expected Peak Oil to ‘spook’ the advanced economies. In particular, I tried to pose the question as to what our economy(ies) might get to look like without yearly ‘growth’.

It seems strange to remember that when we had just started our family in the late 70s, the UK economy was about half what it was to become by 2007, although smaller yearly growth in GDP per capita and a very unequal distribution via real incomes makes the ‘growth’ result feel smaller for most citizens. (Average UK long term GDP growth at ~2% since 1955 when world oil began to transform our ‘coal economy’ gives a doubling time of a little under 35 years?)

Perhaps we begin to see the picture of non-growth. The UK economy is stalled below the 2007 ‘high’ after what is now 5 years. Despite the ongoing recession, however, we are still close to that earlier all-time high. Can we maintain a plateau in terms of what the economy delivers on average personally? And if so, for how long will it deliver? And what, and who, falls off the end first?

Looking around here there are mixed signs. Flow in and out of airports, traffic on the roads, emergency services, even street lighting, and congestion in London, roadside grass trimming, appear to be all maintained, although road quality is not what it was in many places. Some things we thought might happen because of capital investment and capital inflows seem stalled along with construction. Nuclear power is an interesting case in point. Employment, especially for young people has significantly deteriorated (~20% of those under 25 without a job). Services, particularly public services for children and elderly are contracting. The police and prisons and the (public) health service are increasingly privatized and the army will increasingly rely on part-time volunteers. (Our prison population has doubled since early 1990s). We will pay more for the now-privatized ‘public’ utilities, including water, and other services on a trend that started before the 2007 GDP apogee. Many pension provisions on offer to those in early career, especially company ‘final years’ pensions were slowing, have stopped and will not happen anymore. Benefits of all kinds for those out of work or disabled are cut. Incentives for education are cut.

The above is not an exhaustive account. Our economy has shadowed that of the USA, more so than that of rest of EU it seems, for several decades, but all advanced economies face similar futures if the last 5 or 6 years are indicative. So far this has happened here in UK without massive decline, but examples in parts of EU are not encouraging. Youth unemployment of 50% in some of those countries is not sustainable!

I found long term data sheets for UK GDP here http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2009/nov/25/gdp-uk-1948-growth-economy

And an intriguing review of data of UK economic performance leading to and since 2007, with international comparison with USA and EU partners is here http://cep.lse.ac.uk/conference_papers/15b_11_2011/151111_UK_Business_slides_final.pdf

Phil-

Thanks for your detailed comments on the situation in the UK. I think that there has been relatively been more growth in the US than in the UK, but that varies a lot, with Detroit and the “Rust Belt” very much contracted in size, and some cities, particularly in farming areas and oil and gas extraction areas, doing better. (Higher prices for these things, etc.)

It seems to me to be a question of how well the finance industry holds up in Britain. If it implodes, then there will be a quick slide down to a lower level.

Gail,

Very clearly said. My only quibble (not really a quibble just a concern) is that we should be doing this kind of analysis not on raw oil extraction rates, but on net energy per capita (NEPC) rates. My own rough estimates indicate that NEPC actually reached a peak in the mid to late 70s and has been in steady decline since then. Since it is NEPC that is the real energy input to the economy (and real GDP) then I would think we would see something a good deal more dramatic in such an analysis. I take oil extraction rates (and, in fact all liquids production rates) to be a first approximation of the causal effect you are demonstrating. But to get a better handle on the real impact on the economy of energy declines we have to consider both raw energy extraction and the peaking thereof and the declining EROI that results in the declining NEPC rates.

I realize this might be extremely difficult. I am not skilled in the approaches it would take to glean the necessary data from historical records. I’ve always looked at it from the theoretical side, as you know. Still I long to grasp what the real energy-economy situation looks like beyond just the declining rates of extraction.

Some of your readers might be interested in several of my latest posts at Question Everything. I have started a series that examines the many global forces that are systemically threatening civilization. My intent is to show how they are interrelated as a global system, and, thereby, discover reinforcing feedback loops that might hasten the collapse of civilization. I’m not concerned with showing this as a warning or prescription of what to do to prevent it. Rather I am interested in having a better idea of the overall rate of collapse and what that might say about the reactions we humans will have to it. In What Am I Watching I outline the overall systems approach to this project. In then second post I examine your favorite topic (!) Watching the Financial System

George

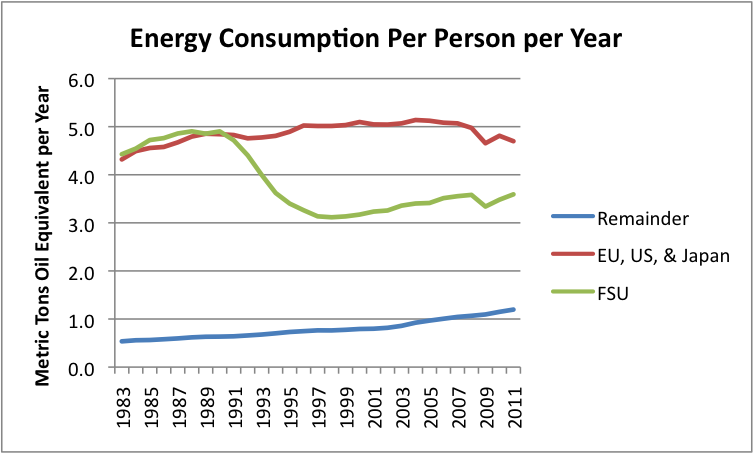

There are very different net energy per capita trends comparing US and Europe, to the rest of the world (or at least, gross energy per capita). Much of the world has really been ramping up coal consumption–much more rapidly than the world has been adding people. This is a chart from my recent post The Growing Part of the World in Charts.

[caption id="attachment_29528" align="aligncenter" width="448"] Exhibit 12. Energy consumption per person per year, in metric tons of oil equivalent, calculated by dividing Energy Consumption shown in BP’s 2012 Statistical Review by EIA’s population estimates.[/caption]

Exhibit 12. Energy consumption per person per year, in metric tons of oil equivalent, calculated by dividing Energy Consumption shown in BP’s 2012 Statistical Review by EIA’s population estimates.[/caption]

I showed this chart in World Energy Consumption since 1820 in Charts.

[caption id="attachment_16921" align="aligncenter" width="448" caption="Figure 10. Year by year world per capita energy consumption, based on BP statistical data, converted to joules."] [/caption]

[/caption]

I am pretty sure that the 2011 value on a gross basis is higher than the 2010 value, since total energy consumption for the world is up 2.5% in 2011 relative to 2010.

According to BP, energy consumption grew by 296.8 million metric tons between 2010 and 2011. Of this growth, 192.3 million metric tons of oil equivalent was from coal. I expect the EROI of coal is higher than that of other fossil fuels. When the changing mix of fuels is taken into account, the EROI trend is less obvious.

Correct me if I am wrong, but doesn’t the consumption figures include that energy used to extract energy? In other words, the apparent increase in energy consumption per capita includes the energy that is not net to society but actually gross (e.g. simply a BTUs per barrel or per ton (coal)).

If that is the case then we still don’t have a good account of the true net energy per capita numbers to assess the impact on the consumer economy.

George

That is true. We don’t have a good accounting of the energy to be making energy. If that were included, it may be that the world is past peak energy.

Part of my point is that different parts of the world see things quite differently, so that what looks like peak energy to the United States and Europe looks quite different elsewhere, if they are able to use more energy than ever in the past.

Gail

It seems to me that data on per capita trends might be useful. For example, if GDP is growing at one percent per year, but the population is also growing at one percent per year, then the amount of GDP available to pay an individual’s pension is not growing at all. Therefore, every dollar that a person expects to get in a pension must be saved while the person is working. And since there are no truly safe investments where the money can be stored, then the whole idea of saving for pensions becomes suspect. I recently noticed that the head of AIG predicted that, once the financial dust settles, retirement ages will tend to be around 80 (I didn’t examine the story very closely, I am afraid.)

If GDP per capita is actually shrinking, then the rational thing to do would seem to be to hoard the money (perhaps as a precious metal) rather than subject it to the vagaries of the financial markets. This behavior would make it very difficult for the younger generation to get started in life as there would be no money loaned by the ‘prime of life’ generation.

So a perhaps reasonable scenario is that a Peak Oil climate will lead to a failure to invest in much of anything beyond a homestead.

Does this thinking make any sense?

Don Stewart

PS My thinking holds a lot of things constant. For example, I assume that corporate earnings will not continue to increase as personal incomes fall by a like amount.

When I talk to US Social Security actuaries, they tell me that as a practical matter no pension plan that covers a large share of retired people can be funded on anything other than as a pay as you go basis, because the amount of funds involved dwarfs any stock or bond market. Pay as you go is the basis underlying the US Social Security system, and pretty much every other countrywide plan.

The way a pay as you go system works is that the taxes paid in this year need to pretty much pay for benefits to those getting the retirement benefits now. So an actuary needs to figure out what portion of the population is retired, what portion is paying in taxes, and collect enough taxes from those who are working to pay for those who are retired. The whole system works best when population is growing, so there are lots of people paying in to support the older people. (Terrible for the earth, though!)

The US program has a “little” smoothing involved, to try to smooth out the baby boom problem, but as far as I can see, that approach simply doesn’t work, because the Federal Government takes the $$ and spends it, regardless, so the plan ends up being funded by US government IOUs, and interest on those IOUs, to the extent that it is prefunded at all.

I don’t know whether hoarding is a useful strategy. It would have to be done by a very small percentage of the population, and be done using something like metals (precious or otherwise). As a practical matter, many of the services an older person needs can’t be bought at any price. What a person really needs is a person with a job to help them out, and that is the reason having enough children so some will be around until adulthood has been so popular, throughout the ages. There wouldn’t be enough precious metals for many to follow this strategy.

I think that the amount of investment that we are doing today will come to an end soon. People will build a simple home, without the benefit of a mortgage or running water, near the land where they plan to farm is located. Businesses will either use existing buildings, or do something equally simple. Governments may tax, so that current taxes can play for current infrastructure needs–roads, for example. Without fossil fuels, much of the mining we do today will become impossible, so it will come to an end.

Gail

Eleanor Roosevelt understood that Social Security would have to be funded in real time–the working generation paying for the benefits of the retired generation. But I was thinking also of things such as retirement plans sold by insurance companies. For example, some years ago I purchased an Annuity which permits me to withdraw 6 percent of the base amount each year, with a ‘guarantee’ that the base amount will never be less than when I purchased it. No surprisingly, the insurance company is taking a bath on this one. The initial investment has NOT earned 6 percent per year.

But as I reason it through, IF an insurance company believed that GDP per capita would not grow, then they would not be willing to offer any ‘guaranteed’ return. In fact, they would probably offer a negative return (like the Swiss are currently) just for holding your money. In short, a whole industry and way of thinking about retirement will be destroyed.

Since you are an Insurance Industry Insider, and thus blessed with not only tremendous analytical skills but also wisdom about their financial situation, perhaps you can give all us Annuity holders some good advice about the precise moment we should all trade in our ‘guarantees’ for some hard cash.

Don Stewart

I’m not good on when to trade in, because I think the “good hard cash” has some problems as well. I am not sure trade-in is really an option on some policies, either.

If you are getting the 6%, I would tend to keep taking it, as long as possible. There is at least some possibility of bail outs. The US bailed out AIG, earlier, and they were a big annuity provider.